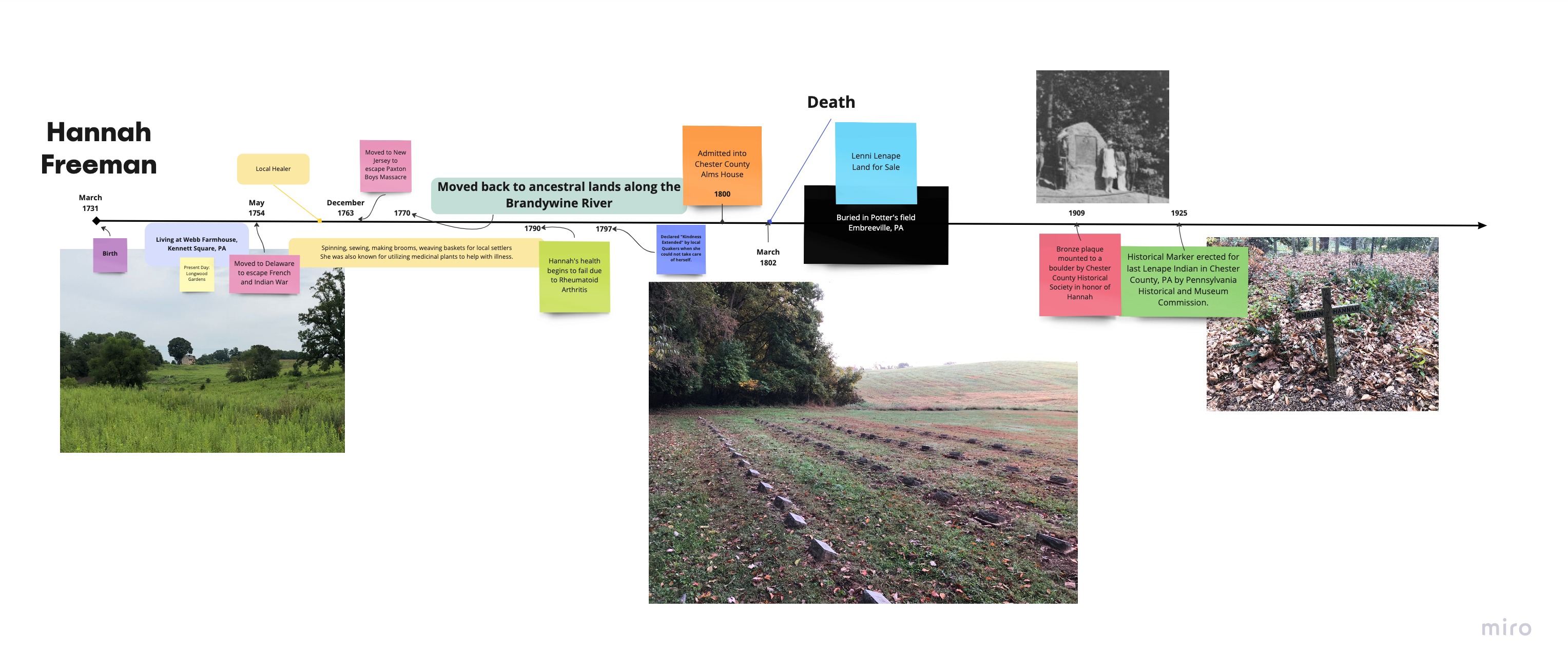

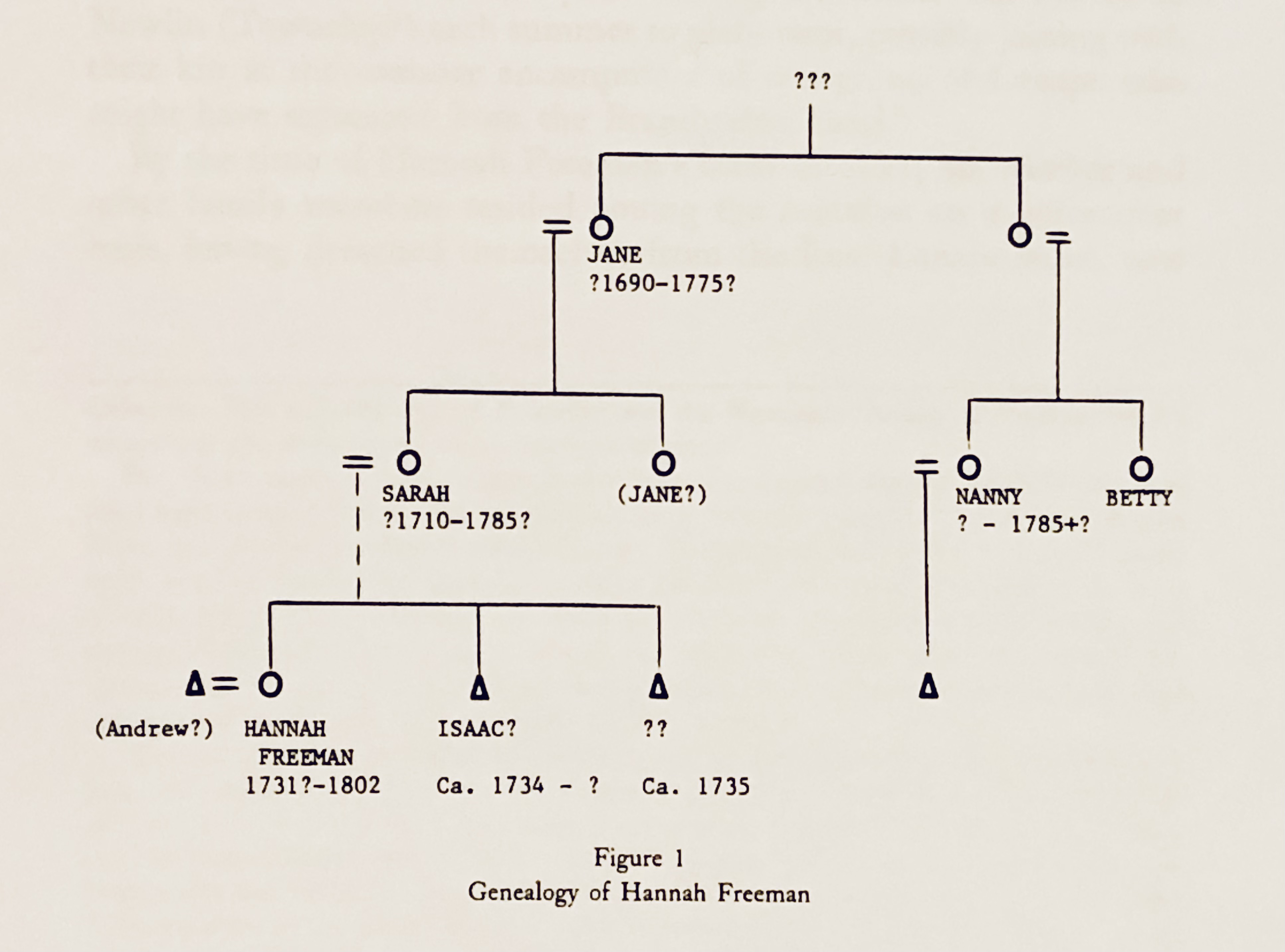

"The Examination of Indian Hannah, alias Hannah Freeman Who saith that She was born in a Cabin on William Webb's Place in the township of Kennett about the year 1730 or 1731. The Family consisting of her Grandmother Jane Aunts Betty and Nanny. Her Father and Mother used to live in their Cabin at Webb's place in Kennett in the Winter and in the Summer moved to Newlin to Plant Corn–She was born in the Month of March. The family continued living in Kennett and Newlin alternately for several years after her birth as She had two brothers born there younger than herself. The Country becoming more settled the Indians were not allowed to Plant Corn any longer her Father went to Shamokin and never returned. The rest of the family moved to Centre in Christiana Hundred, New Castle County and lived in a Cabin on Swithin Chandler's place they continued living in their Cabins sometimes in Kennett and sometimes at Centre till the Indians were killed at Lancaster soon after which, they being afraid, moved over the Delaware to N. Jersey and lived with the Jersey Indians for about Seven Years after which her Granny Jane Aunts Betty and Nanny her Mother and Self came back and lived in Cabins sometimes at Kennett at Center at Brinton's place and at Chester Creek occasionally as best suited. This mode of living was continued till the family decreased her Granny died ab[ove] Skuylkill her Aunt Betty at Middletown, and her Mother at Centre. . . . she lived about two years worked at Sewing and received 3 / 6 [three shillings, six pence] per week wages . . . she worked a few weeks in some other places at Gideon Gilpins then went to her Aunt Nanny at Concord but having almost forgot to talk Indian and not liking their manner of living so well as white peoples She came to Kennett and lived at William Webbs worked for her board sometimes but got no money except for baskets, besoms, etc. She lived at Samuel Levis three years that is made her home and worked sometime, Received for her board no wages, but made baskets etc. and staying longest where best used but never was hired or received wages except for Baskets etc. . . ."

Marshall J. Becker, "Hannah Freeman: An Eighteenth-Century Lenape Living and Working Among Colonial Farmers," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 114 (1990): 251-52.

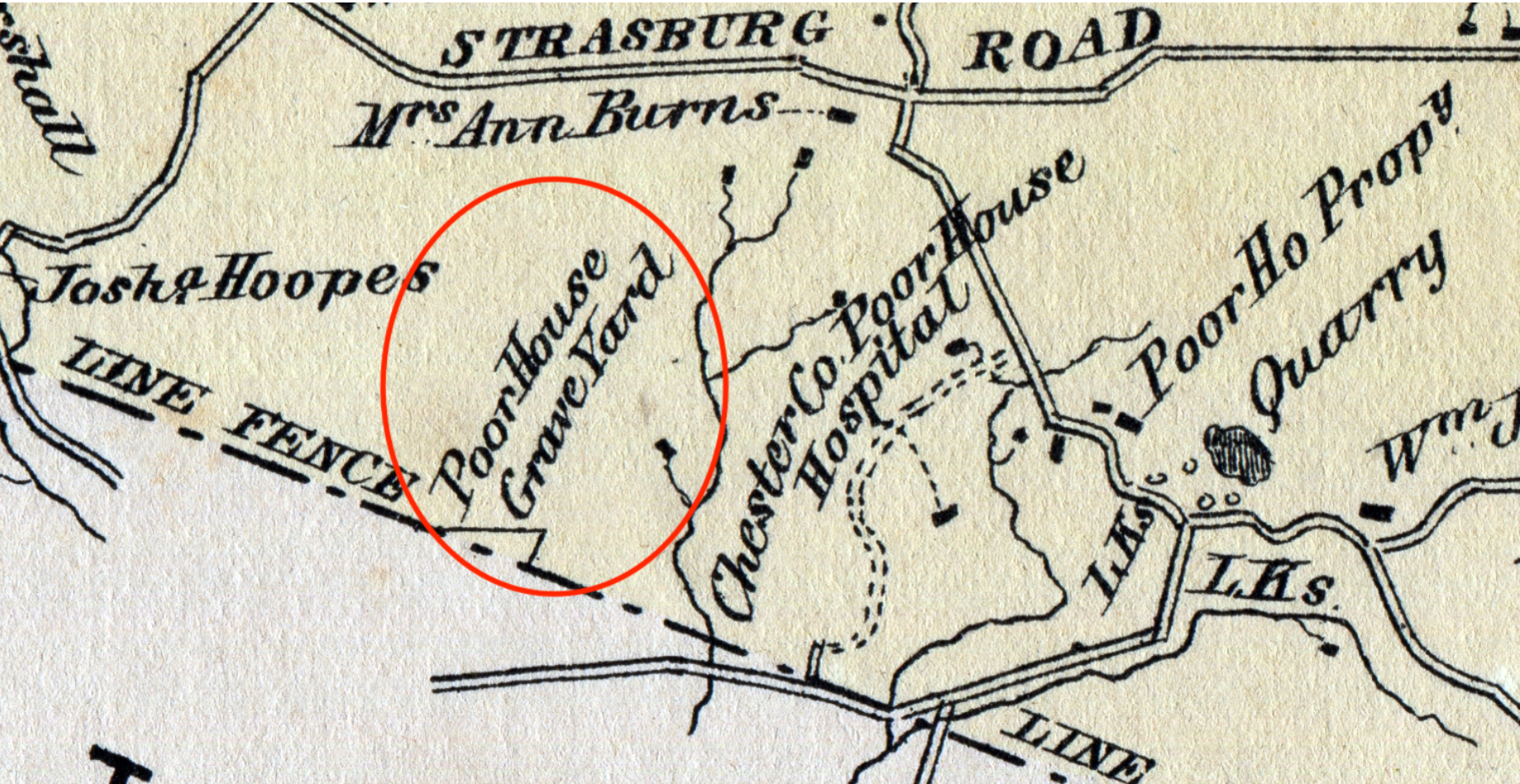

Burial Ground

Unknown headstone.

Prof. John Russell Hayes, original poem on Indian Hannah.

Working mid my marigolds and zinnias,

I found some arrowheads the other day-

Straight I journeyed in imagination.

To an earlier era far away.

When those Newlin Township hills were peopled

By an older, simpler race than ours,

Folk, perchance with little time for musing

Mid low orchard boughs and summer flowers,

Little time to watch the slow unfolding of the silken-petalled hollyhocks.

And the strange and fragrant fascination of pungent peonies and purple phlox.

Or did perhaps those simple forest children

Look with wistful wonder now and then.

On wild daisies dancing on a hilltop

Or Quaker ladies in a mossy glen?

While their fathers tracked the fleet-footed foxes,

Did the little woodland children there.

Gather berry-blooms to weave in garlands.

And roses wild to wind among their hair?

I can picture one bright, dark-eyed damsel.

Roaming often by Wawassan's stream,

Wandering far apart from all her playmates

By those grassy shores to muse and dream.

Happy in her world of winds and waters,

Clouds and leaping fish and warbling birds.

Learning natures secrets through the seasons,

Chanting of her love in liquid words.

In these ancient meadows here about us

Stood the wigwam of her infant days.

Here her father set forth on his hunting,

Here her mother worked their patch of maize.

Here the maiden watched the summer sunsets,

Heard the frozen forest's wintry roar,

Heard the hills re-echo songs of triumph.

As the warriors hastened home from war.

Here she heard the tribal incantations.

Chanted to a wild and wizard tune,

Here she joined the mystic tribal dances.

Underneath the drowsy harvest moon.

And wherever was her future biding,

To whatever valleys she might roam,

Still, she cherished lifelong recollections.

Of those ancient fields, her childhood home.

Now besides the waters of the Wawassan,

Northward from these meadows of her birth,

Lies the last of Chester County's Indians,

Wrapt in slumber in the quiet earth.

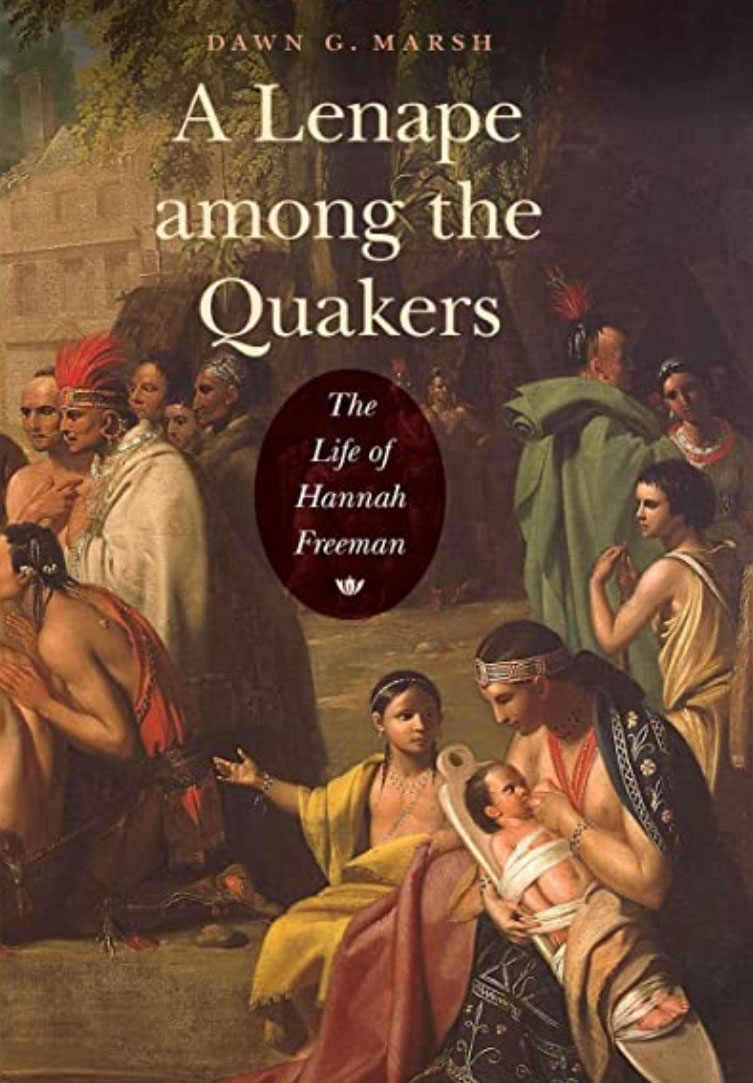

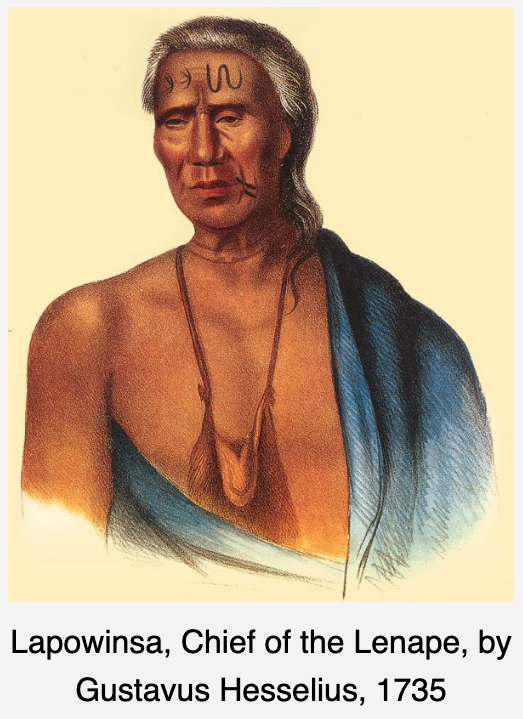

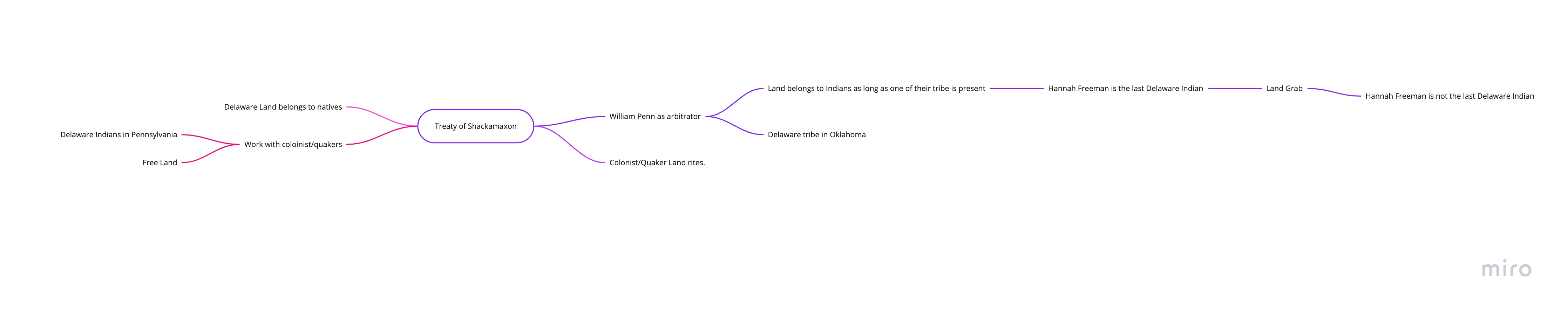

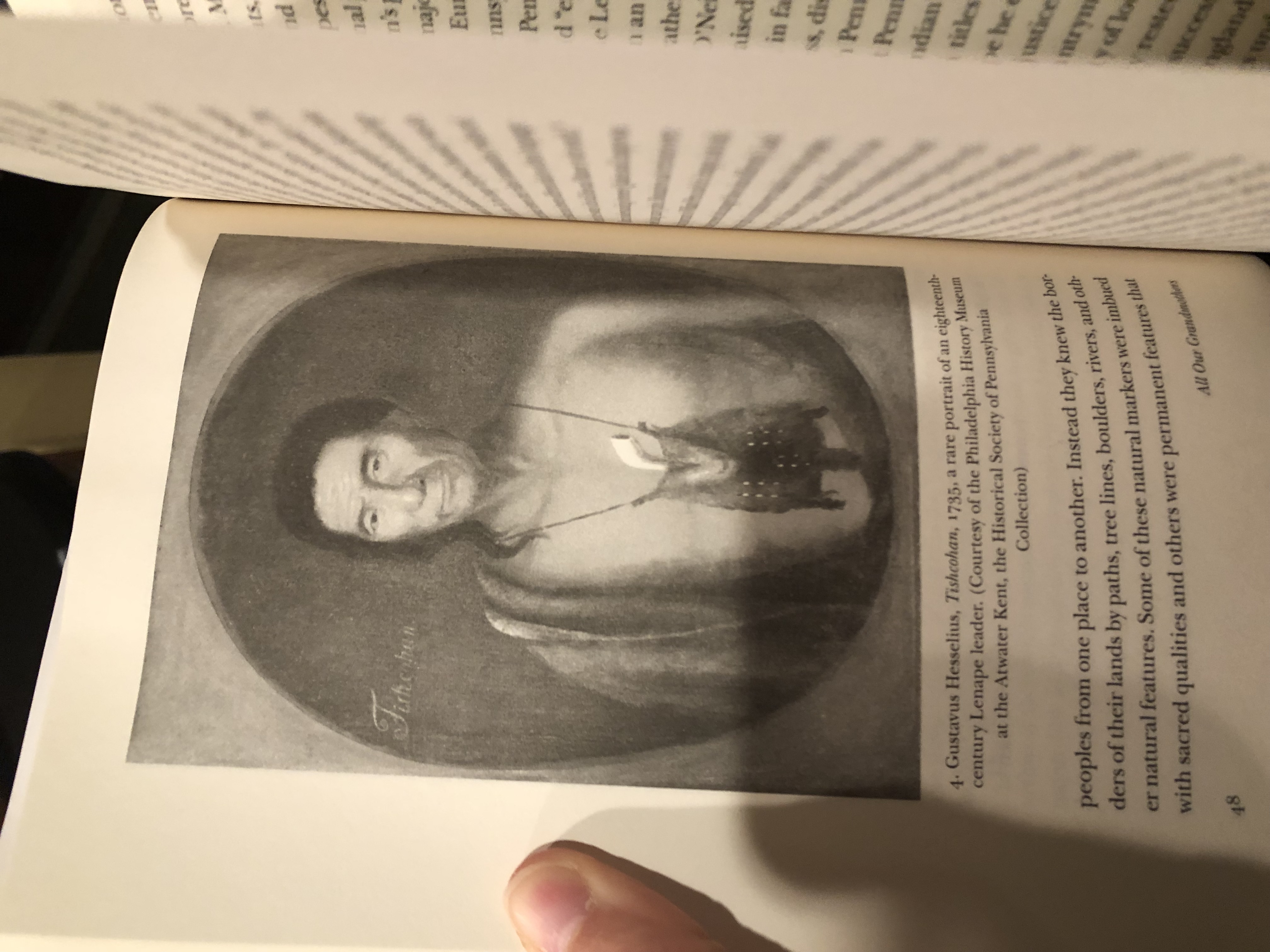

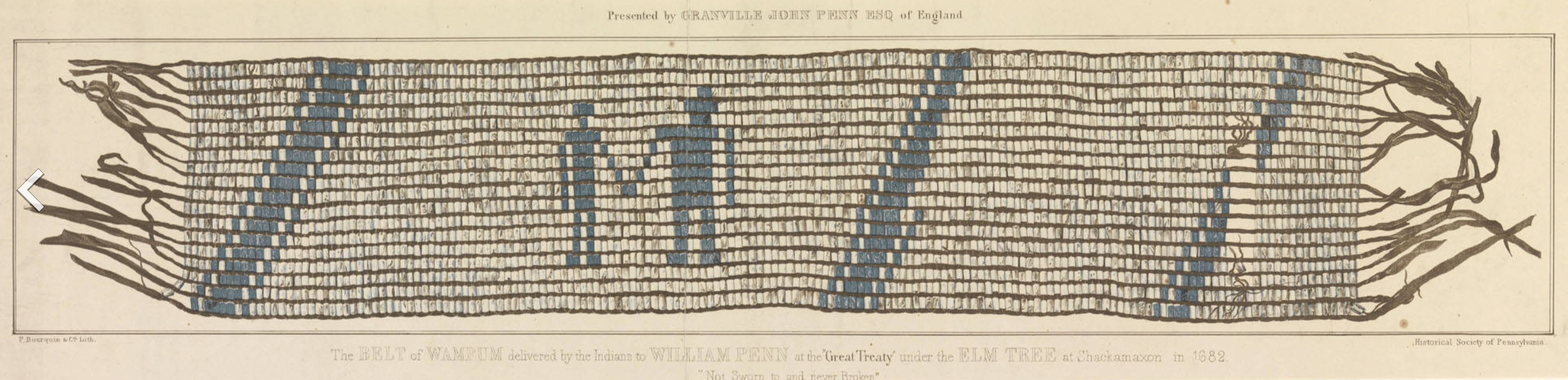

The Treaty of Shackamaxon, otherwise known as William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians or “Great Treaty,” is Pennsylvania’s most longstanding historical tradition. According to the tradition, soon after William Penn (1644-1718) arrived in Pennsylvania in late October 1682, he met with Lenni Lenape Indians in the riverside town of Shackamaxon. There, beneath a majestic elm, they exchanged promises of perpetual friendship. The tradition may well have a historical basis in an actual treaty meeting in Shackamaxon; however, as the term “tradition” indicates, the event is not recorded in original primary source documents, and its details and very occurrence have been debated.

-Andrew Newman, Treaty of Shackamaxon

Pennsylvania is one of a handful of US states that neither contains a reservation nor officially recognizes any native group within its borders. Pennsylvania appears to be the only state without a university-level Native American studies program or cultural center. Within state government, there are commissions on African-American Affairs. Asian Affairs and Latino Affairs, but no state agency represents or acknowledges the existence of Native Americans. Pennsylvania Department of Education standards mandate that students in the third, sixth, ninth and twelfth grade be taught about American Indians, but a survey by the authors of 10 middle and high school history books used in Pennsylvania public schools shows that none of them contains more than a sentence about the Lenape. It could be said that the Lenape have been effectively erased from the Pennsylvania landscape.24

24. David J. Minderhout and Andrea T. Frantz, “The Museum of Indian Culture and Lenape Identity,” Museum Management and Curatorship23, no. 2 (2008): 119–133.

The 1777 Property Atlas organizes land acquisitions during Hannah's lifetime. Comparing the 1777 map to the 1873 map, it appears William Webb gained a great deal of land following Hannah's death in 1802. Just one of the many families that benefited from the Treaty of Shackamaxon.

Mendenhall Family didn't grow much but the land did become documented as plundered in 1994.

The Legend of Penn’s Treaty with the Lenape

by Hannah Chang, Jimmy Wu, Ben Forde, and Ari Kim

Penn’s treaty with the Lenni Lenape is a traditional American tale about the founding of Pennsylvania. As the tale goes, in 1682, under the great elm of Shackamaxon, Penn promised to live with the natives in “openness and love” and as “one flesh and one blood” to which Tamanend replied, “We will live in love with William Penn and his children, while the sun, moon, and stars endure.” Within one generation, Penn’s own sons cheated the Lenni-Lenape out of thousands of miles of land, but the legend continued to grow, popularized by paintings such as Benjamin West’s William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians. Today, the treaty is remembered as a symbol of peace and love.

Some scholars question the factuality of the treaty, as the legend grew largely out of West’s representation 90 years later. The agreement was not a written treaty, though there is evidence to suggest its existence. A Wampum belt depicting two men holding hands suggests a formal treaty between the Lenape and Penn. Now at the Philadelphia History Museum, it was supposedly given to William Penn at the time of the treaty. Andrew Newman writes that though Native Americans did not record in alphabetical writing the same way Europeans did, there is nothing inherently better or worse in the two systems. Furthermore, agreements of peace were often invoked by 18th century Native Americans, though it would suggest that Penn made a series of treaties, contrary to the “Great Treaty” tradition. Early English historians mention treaties of friendships made between Penn and the Natives, and Voltaire famously refers to the treaties between Penn and Native Americans as the only ones that have never been broken. While the treaty tradition may not be accurate, formal treaties of peace and friendship were likely exchanged between Penn and the Lenni Lenape.

While this peace and friendship is what is most commonly remembered in American history, the brief era of goodwill actually ended within a generation. Known as the Walking Purchase of 1737, William Penn’s sons John and Thomas and land agent James Logan claimed to have a sale deed from 1686 for the land north of Wrightstown that a man could walk in a day and a half. Apart from the suspected forgery of the deed, the Penns and Logan also hired three trained men to run a path cleared by settlers. One man ran sixty-five miles, giving a total of 1,200 square miles, far more than the Lenape agreed to. The treaty of goodwill stood at almost 50 years before the pattern of European displacement of Natives continued. The Lenape migrated further and further west for over a hundred years, the majority eventually settling in Oklahoma. Today about 20,000 Lenape live in Oklahoma, with smaller numbers of Lenape people in southern Ontario, Wisconsin, and Delaware.

Dalle 2

Tokkingheads

Artivive App

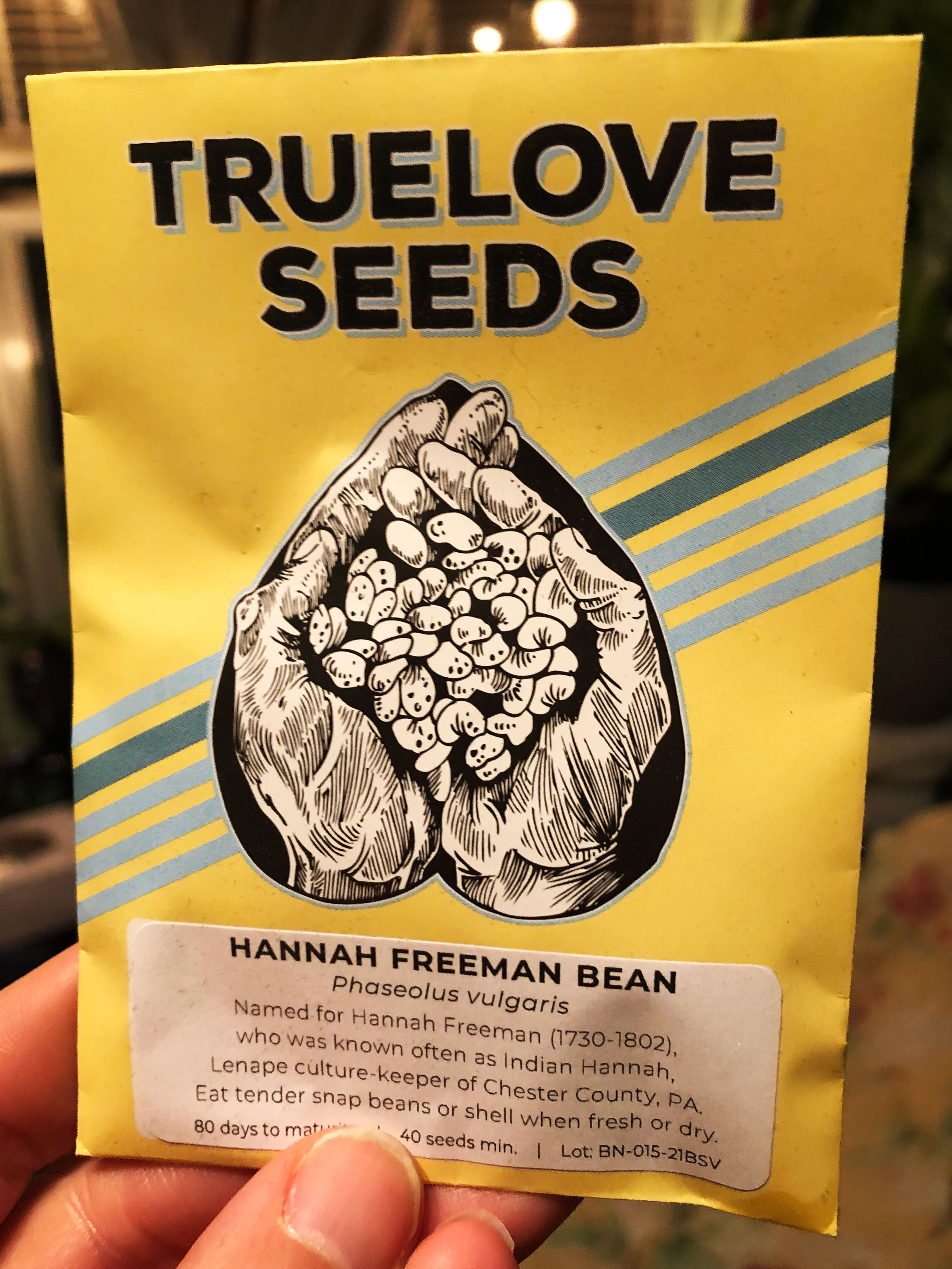

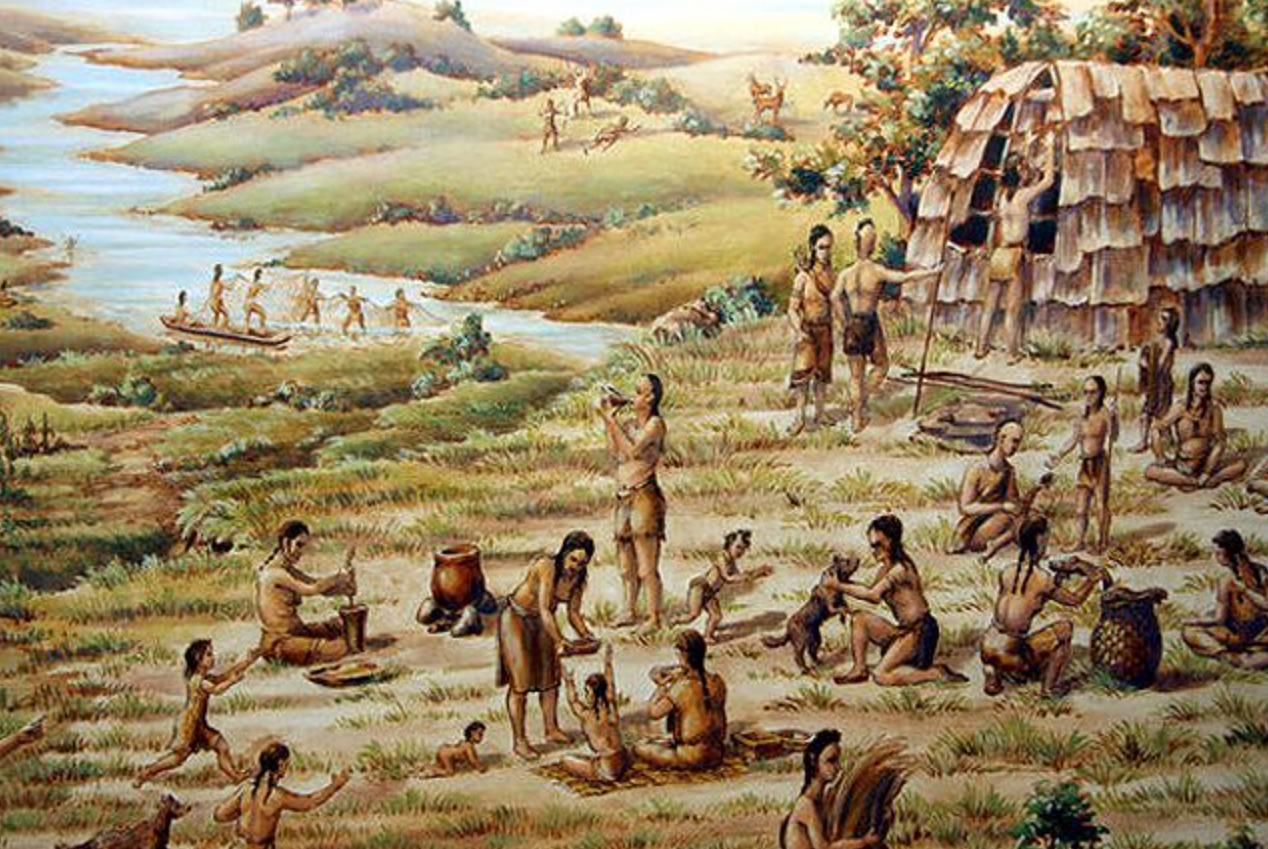

Speculative Future of Hannah Freeman

IN THE YEARS before European colonists arrived, various bands of Lenape (it means “original person” in Unami) lived in an area they called Lenapehoking, which was composed of present-day Manhattan and southern New York, eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey and northern Delaware. At the time Europeans surveyed the area, the Lenape formed a loose confederation of towns stretching from present-day Trenton and eastern Pennsylvania to southern New Jersey and Wilmington. They traded amongst themselves, grew corn and other crops, hunted, fished, crafted stone tools and baskets, and worshipped a single deity, the Great Spirit. Egalitarian and democratic, Lenape society had a matrilineal structure in which women held equal status with men.

When Dutch and Swedish settlers arrived in southern New Jersey in the early part of the 17th century, the mixed society they formed was cooperative and cordial, Lehigh University historian Jean R. Soderlund writes in her book Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn. After William Penn arrived in 1682, he engaged in treaty agreements and land sales with the Lenape; the result was that the Lenape left land that today makes up Philadelphia — the towns of Shackamaxon and Passyunk. At the beginning of the 18th century, the last Lenape land holding in what had by then been dubbed “Pennsylvania” stretched from central Bucks County to the Poconos.

After Penn died in 1718, colonists continued to flood into the region, often settling illegally on Lenape land. Penn’s sons claimed they’d found a drafted deed between their father and the Lenape from 1686 that hadn’t yet been executed — a deed the Lenape insisted they had never seen.

It indicated that the Penns would receive land that stretched from Wrightstown to “as far as a Man could walk in a day and half” — a common unit of measurement. The Penn brothers employed trained speed walkers who made it 64 miles to present-day Jim Thorpe — double what the Lenape likely imagined when they agreed to the deal now known as the Walking Purchase. In 1741, the Iroquois, working on behalf of the English, drove them out, pushing the Lenape west to land along the Susquehanna River and in the Ohio River basin.

Eventually the Lenape would join the French to take up arms against the English in the French and Indian War, but it would be too late. Divided geographically and politically, Lenape factions in central and western Pennsylvania fought on both sides in some of the bloodiest conflicts of the Revolutionary War, while the violence pushed them west into Indiana and north into Canada. About 1,000 Lenape arrived in Oklahoma in the 1860s, and today, the state is home to two federally recognized Lenape nations, the Delaware Nation in Anadarko and the Delaware Tribe of Indians in Bartlesville. Wisconsin is host to the Stockbridge-Munsee, and two more federally recognized Lenape nations reside in Ontario.

Lenape who lived east of the Delaware River retained a degree of autonomy compared to those in Pennsylvania. Eventually most were pushed west, but some assimilated with the New Jersey colonists and purchased land and other holdings. Many converted to Christianity. Though the majority would eventually move to distant regions, the remainder sought each other out and merged with other tribal communities. By the early 1700s, Lenape had gathered near present-day Cheswold, Delaware, and formed communities throughout southern New Jersey in combination with the Nanticoke people of Maryland.

The Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania (LNPA) hopes official recognition will be a way to address the fractured and fraught history of the Lenape in Pennsylvania and reestablish a Native presence in our state. But that same history is why other already-recognized tribes — tribes with a clear through line to the original Lenape population — are so wary about any plans to elevate the status of the LNPA.

-Samantha Spengler

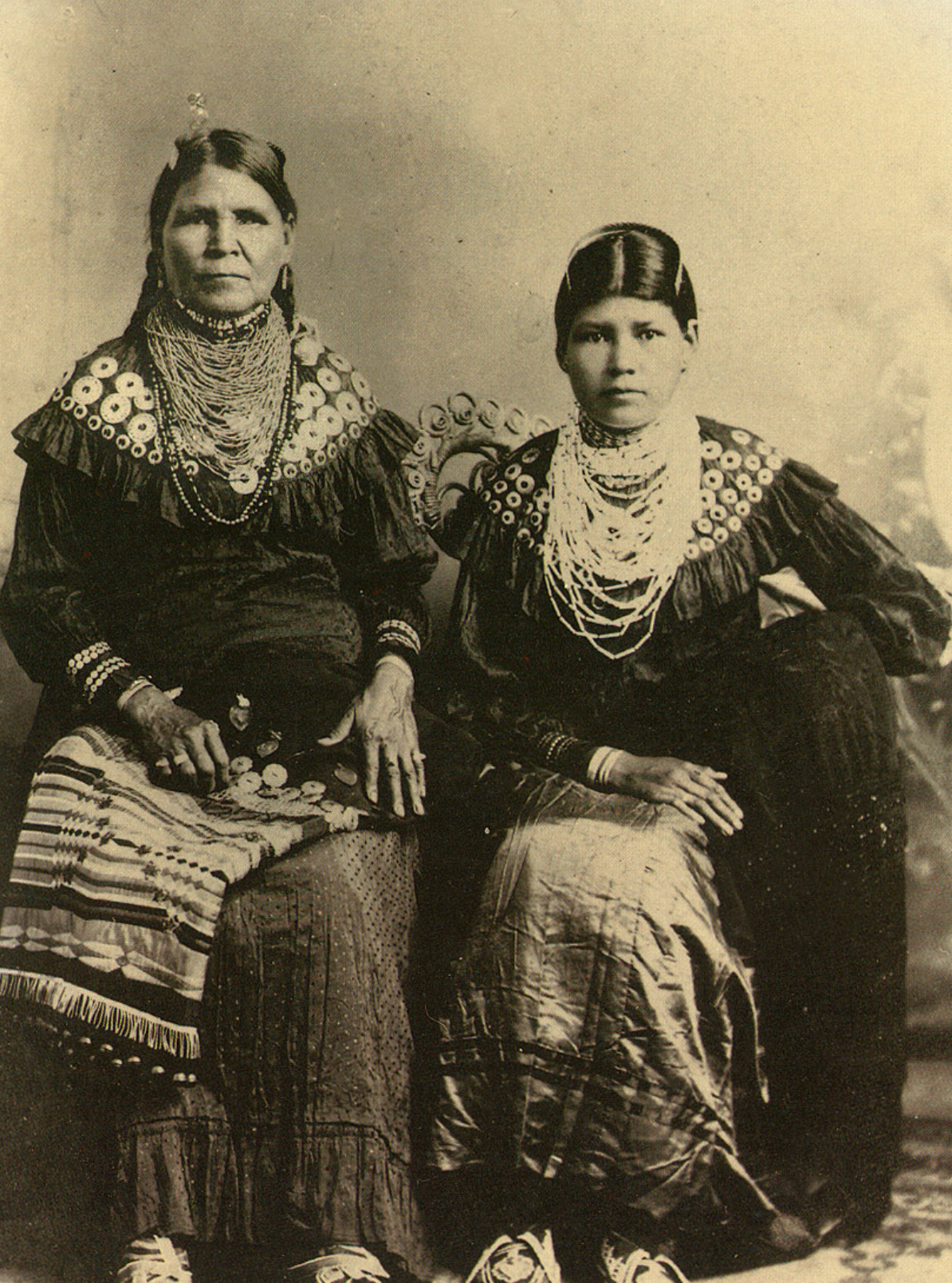

What Hannah may have looked like if she lived into her 90's.

Midjourney AI

ChatGPT

Eulogy to Indian Hannah